Purposeful Listening 6

Analysis/critique

Happy new year, readers and subscribers! Before we get into my interview with Christopher Fox and Patrick Becker, below, I want to remind you that starting next week, I will be publishing extracts from my current book-in-progress. Schubert dub is a memoir-ish meditation on listening and resonance that twines together my journey towards Schubert and a life with chronic illness. It’s going to be a weird, intimate and hopefully poetic journey. I’m excited to be sharing it with you. The first two or three posts will be free to all, but after February they will be available only to paying subscribers. If you’re keen to follow the story (and believe me, even I don’t know everywhere it’s going yet …) then hit the button below. In the meantime, please enjoy my interview with Christopher and Patrick.

About halfway through last year, rumours began to spread that Cambridge University Press – which had been its home for more than two decades – was going to cease publication of the esteemed new music journal Tempo.

Tempo is the world’s longest-running English-language periodical on contemporary music. Originally founded by Boosey and Hawkes in 1939, as the brainchild of former Arnold Schoenberg pupil Erwin Stein, it began life more or less as a promotional mechanism for Booseys composers. (As well as a vaguely philosophical essay on ‘Music as a Language’ extolling music’s ability to serve as ‘a means of common approach and friendship between nations and individuals alike’,1 the first issue included articles on Béla Bartók’s Contrasts and Edmund Rubbra’s Second Symphony.) In the 1950s, however, it broadened its purview to contemporary music more widely and soon became one of the central sites for critical discourse around new music. The editorship of the late David Drew, from 1971–198 produced some of its finest issues – most notably the Stravinsky memorial issue of 1971, no. 97, which included ten ‘Canons and Epitaphs’, original works of music composed in Stravinsky’s memory by Edison Denisov, Boris Blacher, Peter Maxwell Davies, Hugh Wood, Lennox Berkeley, Nicholas Maw, Michael Tippett, Harrison Birtwistle, Luciano Berio and Alfred Schnittke.

Around 1982, Drew was succeeded by his assistant, Malcolm (Calum) MacDonald, who edited the journal until 2013; among other things, he oversaw the moves first away from Boosey and Hawkes into independent publication, and then again to Cambridge in 2003. It was Malcolm to whom I sent my first contributions to Tempo, beginning in 2003 with an article on the Irish composer Ian Wilson that was essentially my opus 1. (And that inspired, twenty years later, this further stocktaking of Ian’s music.) I’ve subsequently written many times for the journal, and have been for a few years nominally a member of its editorial board – a completely frictionless role that required zero responsibilities and hardly any more benefits.

When I was researching my PhD on Polish and Hungarian music of the 1960s and 70s, Tempo was a valuable resource, Boosey and Hawkes at that time being the main Western European publisher for Hungarian composers.

For Tempo to disappear would have been a disaster for the field of new music criticism in the UK. There are already precious few formal spaces for true theoretical and analytical consideration of new music in this country – newspaper criticism in particular having almost completely died out. Meanwhile, Tempo remains – has become even more so, I would argue, under the stewardship of its current editor, Christopher Fox – a repository of vivid writing on concert music’s cutting edges.

It was thus a moment of celebration when the news was announced, in October last year, that Tempo had been acquired by the independent German publisher Wolke Verlag. As publisher of some of the best literature on contemporary music in both German and English, Wolke will, I am sure, make an excellent steward for Tempo, and give it an essential spur to push it into more creative and experimental terrain – both in terms of what it covers, and in how it covers it.

To mark the occasion, I spoke to Fox and Patrick Becker, Wolke’s Managing Director, to get a sense of how we got here – and what comes next. Our conversation took place over Zoom in late November, and as well as Tempo’s move to Wolke, we talked about the necessity of a rich critical culture, the role of musical examples, the balance of the analytical and journalistic, and how to acquire a global view of new musical culture. The text below has been edited for length; both Christopher and Patrick made changes after the interview for clarity.

The first issue of the new Tempo is already online, and will be available in print on 15th January. If you would like to subscribe, you can do so here. Subscriptions start at €36.00 for digital only and €60.00 for print, with discounts for students and separate institutional rates.

TRJ: Christopher, if we could start with you? Could you give me as much of the backstory of how we got to where we are now, and how the Cambridge University Press part of the story tailed off?

CF: The long version is that Tempo was published by Boosey and Hawkes until some point in the 80s. Malcolm MacDonald, who was the editor, took it into independent publication, and then in the early 2000s he made an arrangement with Cambridge University Press and they took over publication

I think it’s fair to say they looked after it really quite well in their own manner. But the journal became part of a portfolio of many, many academic journals. Ten years ago I came along – after Bob Gilmore [Tempo’s editor between 2013 and 2015] died – initially just to look after the journal for an issue or two, but I enjoyed the experience so much that I’m still doing it now.

In the summer of 2024, I had a Zoom with two of the people at Cambridge and they said, you know, the journal is very successful, there are lots of subscribers, we love everything you do, but unfortunately, it no longer fits the evolving business model of academic publishing at Cambridge, which is based on moving towards open access as much as possible. Open access involves authors of research paying to have their work published and Tempo has never been that sort of journal. A lot of the people who wrote for Tempo were willing to write their articles for free, but they weren’t necessarily employed by academic institutions who could then pay for open access. Or if they were employed, they were not necessarily mainstream researchers in their institutions.

Cambridge University Press said, very politely, that they were going to cease publication in October 2025 and that they would look for other publishers. It’s probably not giving away any secrets to say that I might have helped them in that process. About a year ago, Patrick and Bastian Zimmermann and I made contact, initially to talk about a collaboration around the work of Éliane Radigue for the Positionen magazine, and I let Patrick and Bastian know that Cambridge’s involvement was finite. Gratifyingly, they were immediately very enthusiastic at this prospect, one thing led to another, and here we are.

TRJ: That seems like a good point to turn to you, Patrick. Obviously, you’re coming at this from a European rather than a UK perspective, you’re slightly the outsider. What is the significance of a journal like Tempo for you? What was it about that idea that made you and Bastian sit up and listen?

PB: The situation in Germany is certainly different from the UK or the US. Here, we have journals like Positionen or MusikTexte, that are, in some ways, comparable. However, one of the central things about Tempo is that there’s nearly 80 years of journalism about contemporary music that has been covered by this journal since its foundation by Boosey & Hawkes in 1939. You are looking at decades of documentation and debate in Tempo, and that’s something quite exceptional.

At the same time, independent music journalism in Germany has gone through a lot of structural changes recently – generational shifts, changes in format, questions of funding. That’s fairly typical here in Germany. Despite the constant attack on culture by budget cuts, there’s often still a sense that projects can be continued in a different form, rather than simply disappearing. That background made it feel quite natural for us at Wolke Verlag to carry Tempo forward this way.

What we only really understood once we had access to the data from Cambridge University Press, the previous publisher of Tempo, is how strong Tempo’s readership already is in German-speaking countries. A lot of people read it online already, and many libraries subscribe to it. So it didn’t feel like a one-sided move at all – there is already a real audience and real relationship to us. In that sense, it felt quite mutual.

And then, of course, Tempo is an English-language journal. Over the past years, there’s been a growing effort to rethink how contemporary music is discussed internationally – to move beyond a very Eurocentric or Northern-Hemisphere-focused perspective. You can see that in concrete developments, like the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation awarding one of its 2025 Ensemble Prize to the Tacet(i) group from Thailand, or the Chilean composer Francisco Alvarado being featured at the Donaueschingen Festival last year.

Those are signs that contemporary music is increasingly understood as something much broader than just Europe, the UK, or North America. And in that sense, it feels like a very good moment to continue Tempo – and to develop it as a space to reflect on what contemporary music actually means today, especially in a digitised and globally connected world.

TRJ: I guess the same question to you, Christopher. Where do you see Tempo fitting within the landscape of contemporary music criticism? Because it exists in a strange space somewhere between academic research and journalistic criticism and, at least within the UK, nothing else really compares to that.

CF: I think that’s right. I’m not sufficiently a historian of music writing in the UK to understand quite why this happened, but I first read a copy of Tempo sometime in the early 70s and it has always been like that. There has always been a balance between quite serious, analytical articles and more journalistic – but serious – reviewing.

In retrospect, I think one of the problems with the Cambridge period was that because Tempo was perceived as an academic journal, there was probably more writing submitted for the front half of the journal that was trying to be academic in a not entirely satisfactory way. The writing was academic at the expense of actually writing about the music. That’s something that I have been trying to redress, and the first issue with Wolke already goes a long way towards achieving that rebalancing.

Because there’s absolutely a need for really serious writing, and there have been many attempts to create something similar to Tempo. In the 80s, I was involved with Contact, which similarly had quite thorough analysis of new work.2 But as Patrick was saying, the thing that has developed in the last twelve years – because it was something that Bob was already conscious of in his brief time as editor – was that we need to move out from this very strongly Euro-centric, and before that UK-centric, view of new music.

It’s not that easy to do, but I think we do have a much wider pool of writers who are prepared to write about a much wider range of things. And of course, the other thing that has changed is the gender focus, in that fifteen years ago, most of Tempo was about music by men, and most of the writers were men. That has changed radically and will continue to develop in a positive direction, I hope.

TRJ: How are you going about that widening that global horizon? Are you gathering writers who are based in, say, Indonesia, South America or wherever?

CF: One of the things that’s happened in the last four or five years is that we have much more writing from China, for instance. And I think word spreads.

I haven’t been to China, but I’ve made lots of contacts. And we now have a bigger editorial team and a much more active publisher, if I may say so. We all meet people and go to things. Even if you go to a European festival, there are likely to be people there from other parts of the world. And our contacts are acting as nodes in the various territories where they are based.

It’s worked much more successfully than I thought it might when I wrote an editorial – I think before COVID, actually – that was essentially saying: we need to know more about what’s going on, because unless we know more, what we do is impoverished.

PB: What we are trying to do systematically is – and we’re trying to install this right now – something like a network of correspondents that we call ‘editing contributors’. What we’re trying to do there is to achieve some kind of diversity in this network of correspondents under different criteria, definitely also geographical, so that we try to have some international people. They don’t have a position at the journal as such, or they don’t need to write. But if they see something in the area where they live, for example, let’s say, somewhere in South America – in Chile, for example, Santiago has a wonderful contemporary music scene; or, for example, in Shanghai or Beijing – then they can get in touch because they we already have this established contact and they can say, listen, there is a nice concert, there’s a good festival.

And at the same time, what they do – and this is the reciprocity there – is that, for example, let’s say someone sees a concert or learns about some kind of event and can’t go there themselves, they can say, I know someone here who would be willing to write. Also, looking towards really supporting early career writers, and maybe still graduate or even undergraduate students. So to really go in this direction, to help us. Because of course, it’s impossible in a way to have this global scale, even with the bigger core editorial team, because there’s just so much going on.

But I think if we use this as something like the extension of what we do in the core, what the editorial team of Tempo does, then we can have a more systematic and more effective way of really trying to open up the view. I mean, it’s not just about documenting, right? Of course, we want to document through the longer texts and interviews and also the review section. But I think what will really help reinstall Tempo as a journal that covers global contemporary music is inspiring thought, discourse, and so on in all areas of the world.

Because otherwise it’s just an archive – and Tempo has a very big archive, which is very nice – but I think it really should be about mutuality also.

TRJ: And you want it to be a place that invites discourse rather than, as you say, just reports.

PB: Yes.

TRJ: With respect to this global, or wider world view, are there other things that you are trying to set up that maybe Tempo wasn’t doing before?

PB: I think the most important thing – and Christopher will probably agree – is the new design. That’s really central. From the looks of it, under Cambridge University Press given the subscriber structure and the way Tempo was handled institutionally, it was mostly thought of as an academic journal.

We have a very different understanding of what Tempo can be, and what it should be, as a magazine about contemporary music. All three of us here know that it has never really been just an academic journal. So one of the first things we wanted to do was to reflect that understanding very clearly in the visual and material identity of the journal.

That is why we have been working with NODE Berlin Oslo, a wonderful graphic design studio that has a strong connection to the contemporary music scene. They also design the Field Notes magazine by INM in Berlin and work together with the Ultima Festival in Norway. So they’re very used to thinking about how contemporary music presents itself – not just visually, but culturally.

As we are speaking, the new design is almost ready to go to print now, and we’re genuinely excited about it. Of course, library subscriptions – they often make a journal financially viable, and those readers primarily access Tempo online. But at the same time, we’re consciously trying to re-establish Tempo as a journal for the scene and by the scene. And for that, the physical object of a printed journal matters immensely: the haptics, the feel of paper, the sense that this is something you want to hold, keep, and return to.

At the moment, that’s actually one of the difficulties for us. We are asking people to renew their subscription or subscribe anew, while much of what we’re doing is still not visible yet. It’s a bit – well – like a cloud. A Wolke, in that sense. You’re asking people to trust something they can’t fully see yet.

That’s also why we wanted to create a moment of introduction, or a kind of reveal in mid-December. Not only of the design, but of ourselves and of the direction we want to take with the journal. On 15 December we held an online meeting where people could meet the editors, hear how we think about Tempo, and get a sense of where the journal is heading in the first issues. For us, that was really about approachability – about inviting people in, rather than presenting something as already finished or fixed.

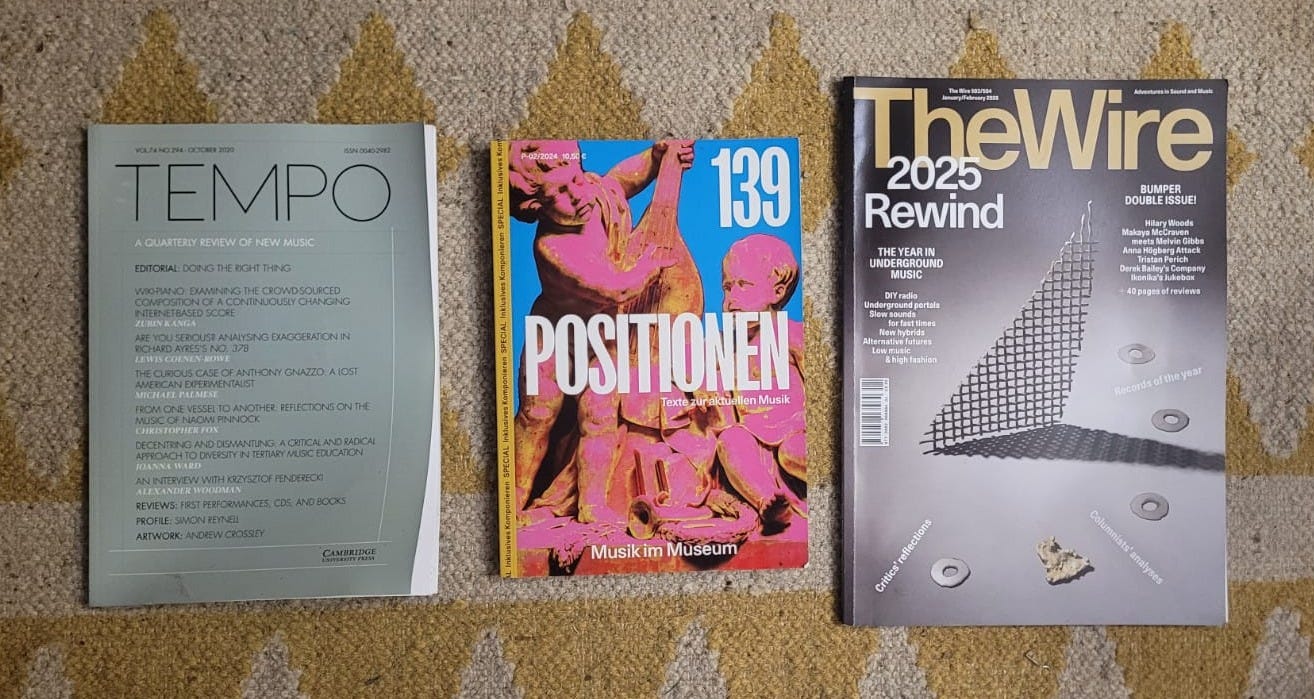

CF: Maybe I’m superficial, but I think if something looks dull it’s a real effort to feel excited about it. And Tempo did look dull. It looked much more boring than The Wire, more boring than Positionen. Journals about the visual arts look more exciting and there’s no reason why that should not be the case for us. And the work that the people at NODE are doing is already really exciting.

So the journal will look like something you want to have and, if you buy it in print, you will want to keep.

TRJ: Yeah, I’ve got boxes of old issues down here behind me ...

CF: I spend so much screen time every day and I don’t read on screen for pleasure.

TRJ: I haven’t seen what it looks like yet, but there are design challenges that are different for new music. If it’s an architecture journal or a visual arts journal, there’s obviously lots of lovely things you can illustrate. How are you addressing that within a new music context? Because music isn’t always very visual, which is the point.

CF: In the January issue, we have a lot of great photographs, because music in performance often looks interesting. And – to be terribly nerdy – I think music examples look interesting too, little kernels of musical truth scattered across the pages. And there aren’t enough of those in contemporary writing about music.

PB: I also think there’s been a tendency to use less of them.

TRJ: I suppose that speaks to where you’re pitching your audience. You don’t get musical examples in The Wire, for example, because it’s not, generally speaking, or pointing itself in the direction of a notationally literate audience. But presumably you are thinking of Tempo having a musically literate audience. Positionen I don’t think ever really does music examples …

PB: Well, the generational shift at Positionen also entailed a broader shift in the content and in the visual direction of the whole journal.

But I actually think this is one of Tempo’s real strengths: that it can still be a journalistic or magazine-format space where music examples are possible. At the moment – as you say yourself – I don’t really know any other independent music journalism outlet that still does this in a non-academic context. And I do think there’s a real demand for it. I think that’s because they speak to composers and performers on a level that’s different from music journalism that focuses primarily on discourse. There’s still a strong – and maybe even growing – interest in the technical and compositional side of contemporary music.

And that doesn’t really have many places within independent music journalism at the moment. Partly because it’s harder to market. As you say, The Wire reaches a very large audience. Tempo also has a substantial readership, but it’s more challenging to communicate this kind of content widely, because it can also be intimidating, or off-putting, at first glance.

At the same time, I think we can also rethink what musical literacy actually means. Yes, it’s important that music examples can exist. But that doesn’t mean we’re saying that the only valuable contemporary music is music that’s fully notated – or even that it has to be written down at all.

What matters to me is that Tempo remains open enough to offer a platform where people who do want to work analytically, and who do want to include music examples, can still do so. To be able to say: here, this kind of writing is still welcome. You can still take the time, and the space, to think through music that way. I think that openness is something Tempo can do very well.

TRJ: Yeah, I mean, that idea does appeal to me.

CF: I think different things intimidate different people. Tempo has an unusually musically literate readership. There will be some people whose eyes just skim over the music examples, but the same is true of some of the theory-heavy writing that we’ve published.

For instance, one of the things that we want to carry on with is writing about different temperaments and different ways of organising musical sound. And that involves specialist musical vocabularies, technical vocabularies. I’m not going to say that I haven’t understood the articles, but we have published things that I proof-read for syntactical sense, without bothering too much about whether what was being written was actually sensible.

PB: I mean, the question is: what’s actually scarier – seeing, say Lacan’s graph of desire or the score example of ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’? In the end, they’re both just a graphical representation of something. And both can be intimidating.

CF: We published a piece of music fiction: an entirely invented ethnomusicological study of a community in the northeast of England [‘Seaton Snook and the building of a parafictional seaside town’, by Peter Falconer, Tempo no. 308 (2024), 70–82]. But it sat on a whole body of theory and although some people will have read it and thought, well, this is just silly, because it’s fiction, the same ideas that are embedded in, for example, Jennifer Walshe’s fake archive work recurred in that article.

I think one of Tempo’s roles is to present serious and innovative ideas, but through the medium of really good writing.

TRJ: Yes. Very occasionally, I get people approaching me saying, I’ve written this thing and it’s quite an experimental text or quite a creative text, that is around new music but is not a conventionally new musical text. And they’ll ask if I know anywhere where I might be able to publish this? Is new Tempo going to be a place where I might be able to send that sort of person?

CF: Absolutely. And we have published work like that: more ludic, less analytic.

PB: At the moment, the editorial team consists of Christopher as editor-in-chief, with Ed Cooper as co-editor, Celeste Oram as reviews editor, and Anna M Heslop handling copy-editing. We are also expanding the editorial advisory board with Ty Bouque and Elaine Fitz Gibbon joining.

What that gives us is a genuinely broad editorial base. So when an experimental or unconventional manuscript comes in — something more creative, more ludic, less obviously analytical — it doesn’t land on one person’s desk in isolation. It can actually be discussed. And I think that’s a really good position to be in. We’re very open to receiving work like that.

That’s also one of the real advantages of being independent. You’re not immediately answering to external frameworks or expectations. You can take the time to talk something through, to weigh it, and to make a decision collectively, rather than feeling that something simply doesn’t fit and therefore can’t be published.

For us at Wolke Verlag, a strong motivation behind taking this on was also about continuity – about making sure Tempo didn’t disappear. There were, as far as I know, several interested university presses who could have taken it over from Cambridge. But, as a book publishing house, Wolke is structurally and culturally very different from that world. And we’re also different from most publishing houses in Germany – both in size and because of our subject focus on music. Books on music, that’s our slogan, and that’s what we do.

That focus is niche, but it’s also something we’ve built a lot of experience around during the 45 years of our existence. And we value this independence enormously. You can see how productive that can be when journals or publishers are able to redefine themselves. Independence allows for that kind of momentum, both conceptually and visually.

I also think there’s something important in terms of signalling. If Tempo can continue as an independent journal, especially in the Anglo-American context, where such initiatives are much less common, that sends a message: that this kind of publishing model can still work. In Germany, this is slightly easier because the public funding structure is different. But even so, the signal of continuing Tempo matters, and we have received a lot of feedback suggesting this thinking is right.

In that sense, it feels like a good fit – and also like a continuation rather than a break. There’s a generational shift happening at Wolke as well, and I don’t think that automatically means decline. On the contrary. Not everything has to go downhill from here on [laughs]!

TRJ: So what can we expect to see in the first few issues? Is it going to be a similar format to the old journal, with half articles, half reviews?

CF: There’s an overlap between how the journal was and how it will be. You can’t change things overnight. Well, you probably could …

PB: … That would be a very long night, I’m afraid!

CF: Across the journal as a whole, there’s a spectrum of different sorts of writing. And we will fill the gap between the longer feature articles and the reviews, so in this first issue, there’s a collection of shorter pieces around a long critical review of the 2025 Darmstadt courses by Max Erwin. Max has written about Darmstadt for nine years now for Tempo, and his reviews have become a favourite with many readers.

The first one that we published, during a period when I was temporarily Reviews Editor as well as everything else, was a fantastic piece of writing, but almost as soon as it was published online, I got a very wounded message from a reader who said that, as far as they were concerned, the new music community wasn’t sufficiently resilient to cope with criticism like this. But I think that’s one of the purposes of Tempo: to be sharply critical, but always in a reasoned way, never in a polemical way. If the new music community can’t criticise itself, we really are in the last days. But we’re not. The health of any cultural endeavour is defined by how rich the criticism of it is.

TRJ: When is the first issue, and what can we expect to see in that?

CF: January 15 is publication day. As well as the Darmstadt piece, there’s a wonderful review article about the album Tracing Hollow Traces by Andile Khumalo. We have covered very little music from sub-Saharan Africa and I want to address that. The article is a brilliant piece by Stephanus Muller that considers what it is to be an African composer, so it’s both a critical response to the album and an attempt to explore that question.

I’ve written an article that is also a sort of review article, in that it grows out of Nonesuch’s recent Steve Reich birthday reissues. It focuses particularly on Jacob’s Ladder, because that is Reich’s most recent work, but also compares it to Schoenberg’s Die Jakobsleiter. There’s a fine piece by the Scottish singer, Stephanie Lamprea, about the project she showed earlier this year, a collaboration between her and dance and British sign language and live electronics. And there’s an interview with Steven Takasugi, by Anna M Heslop. Takasugi talks about what he calls ‘new music activism’, viewing his work as composer and teacher in the context of political and cultural resistance.

And then in future issues, we want to look at the relationship between music and capital; it might be called ‘the capital of new music’, or it might not. Another issue will be to do with diversity; not just in the sense of different sorts of balance between gender, ethnicity or class, but also the diversity of practice across new music today.

Because Wolke has enabled us to enlarge the editorial team and to pay authors for what they write, we can plan much further into the future, which is very exciting. Tempo’s existence with Cambridge University Press was much more hand-to-mouth.

TRJ: It also sounds like you’ve got a little bit more editorial opportunity to steer things. From the outside, at least, Tempo always looked a little bit like, ‘Well, we’ve been sent these things, so we will just schedule them in’ ...

CF: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

TRJ: … Whereas this is more commissioning: I want something on this.

CF: Yes. Some of my editorials were just wallpaper: this wall is full of cracks, but you won’t be able to see them by the time I’m finished [laughs].

PB: For us, it’s really important that the editorial team is able to steer the journal. Wolke is independent, Tempo is independent as well – even though it’s now part of Wolke – and that independence only really works if the editors are allowed to do their work without interference. I see my own role, and the role of the publishing house more generally, as providing an umbrella – a platform, infrastructure, and the administrative side of things.

I think it’s also important to say that we had a lot of support along the way, especially by a great team of lawyers from the German firm Schalast, which was needed to make it through eight months of intense contract negotiations with Cambridge University Press. I suppose I speak in Christopher’s and my name here, personally, to acknowledge that this wouldn’t have been possible on our own. There’s a small and very committed group of people who also supported the transition of Tempo to Wolke through donations and fundraising. In that context, the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation was also extremely generous in providing funding outside their usual deadlines. They clearly recognised that his was a moment where support actually mattered.

What was encouraging for us was to see that there really was also a community behind this. In a way, the whole transition was a kind of crowdfunding campaign – deliberately low-key and largely under the radar. But the support is there. We’re already seeing people subscribing, especially individual subscribers, and that’s particularly important to us. Of course, library subscriptions are crucial for the long-term financial stability of a journal like this. But if Tempo is meant to be community-based and community-driven, then it also matters to rebalance the subscription structure – reflecting the vibrant global scene of contemporary music.

Once the first issue is visible – first on screen on 1 January, and then in print on 15 January – it will really become tangible that the new Tempo is here. That will be issue number 315, which is quite astonishing.

TRJ: Other than subscribe, obviously, what is the best way for people to support the journal going forward?

PB: Subscriptions really are the best way. That’s the clearest form of support and the one that gives us the best planning security. And of course, people can also buy individual issues, especially the first ones in 2026, if they want to see where the journal is heading.

Beyond that, we’ll definitely be doing targeted outreach – to people, but also to institutions and organisations in the field. Less so to libraries, and more to places like ensembles and music festivals – simply to spread the word, because advertising for them is also a real option. Tempo has a very wide reach, both in print and especially online, with tens of thousands of article views and downloads every year worldwide. So if someone wants to advertise an event, a project, or a release, they can be certain they’re reaching exactly the audience they want to reach. Tempo is a journal for this particular music scene.

There’s also something less tangible, but still important. We see this with Wolke as well. I’m probably younger in age than in my actual way of using social media, but it does matter a lot. Sharing things, reposting them, drawing attention to an article or a review –maybe just the first paragraph, or a photo when you spot the journal in a bookshop – all of that helps to create a sense of community. It creates a kind of circulation, a feedback loop, where people see something, share it, we reshare it, and it builds a certain atmosphere around the journal. And that atmosphere matters..

We have already established small rituals ourselves [laughs] Christopher and I have developed this tradition of taking selfies every time we see each other – and for reasons I still don’t fully understand, people seem to really enjoy those. So yes, even things like that help to make Tempo feel present and alive!

CF: Heaven knows why, but the last one got nearly 3,000 views. [Note: The transition announcement in October got more than 10,000.]

PB: Yeah, yeah, yeah. There’s a lot of people ...

CF: I don’t think that’s to do with you and me. I think it’s to do with Tempo.

PB: You, me, Tempo, and the Instagram algorithm. I think that’s the Holy Trinity.

TRJ: Was there anything you wanted to add, Christopher?

CF: The important thing for me is that for 10 years it’s felt as I’ve been in a rather dark room with Tempo. Very few things came into the room that didn’t come in through my computer. It’s been very touching to discover that there is a group of people who are prepared to put substantial sums of money into the takeover by Wolke. It’s very reassuring to discover that something with which one is associated is actually held in quite high esteem!

NB: It’s worth mentioning that this optimistic view was expressed in 1939, of all years!

Contact was founded by Keith Potter (my former PhD supervisor) and Chris Villars, and ran from 1971 to 1990. The full run of the journal was digitised a few years ago and is hosted by Goldsmiths College, here. Fox joined its editorial board in 1987. In an editorial for the Spring 1987 issue, Potter described its aim as a ‘sometimes faltering course between the Scylla of the “academic journal”, written by academics and read by no one, and the Charybdis of the “popular magazine”, responding only to current fashion and the “promotional machines” and producing nothing of any substantial musical worth.’

Tempo is essential! I had an article published there during the Calum MacDonald years, a roundup on the 1992 Ultima Festival.