Purposeful Listening 5

Collate/curate

Welcome to the last PurLis of the year! I’ve only been at this Substack thing a couple of months, so while I’ve been enjoying it, I still feel like I’m getting the hang of it. I am therefore so, so grateful to all my subscribers for your support and patience on the journey so far.

Lots of things are in the pipeline for next year, the most significant of which is that, from next month, I will be releasing short extracts from my current work-in-progress book. Tentatively titled Schubert Dub, it is an experiment in entwining: a reverb-drenched braiding together of the music of Schubert and its echoes in contemporary music, and a memoir-ish thread on listening to my body. It is, as I say, a bit of an experiment, and is easily the weirdest and most personal thing I have ever written. It’s also an idea that has been many years in gestation, and if I don’t start chucking bits of it out into the world, it may never come into shape. That makes you lovely people both my spurs and my guinea pigs.

Plates of Schubert Dub will be served up once or twice a month, in off weeks between the regular issues here. And after the first two or three teasers, they will be available only to paying subscribers. So smash that subscribe button if you’d like to read more!

Until then, please enjoy a surprisingly piano-loaded run-down of contemporary classical albums of the year, plus two live reviews from London concerts this November: London Contemporary Music Festival’s one-night-only show, The Composer Is Not Present at Wigmore Hall, and the London Sinfonietta’s return to Gérard Grisey’s Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil, along with music by Cassandra Miller, Rebecca Saunders and John White.

Happy Christmas, and I’ll see you in the New Year.

Tim

Albums of the year

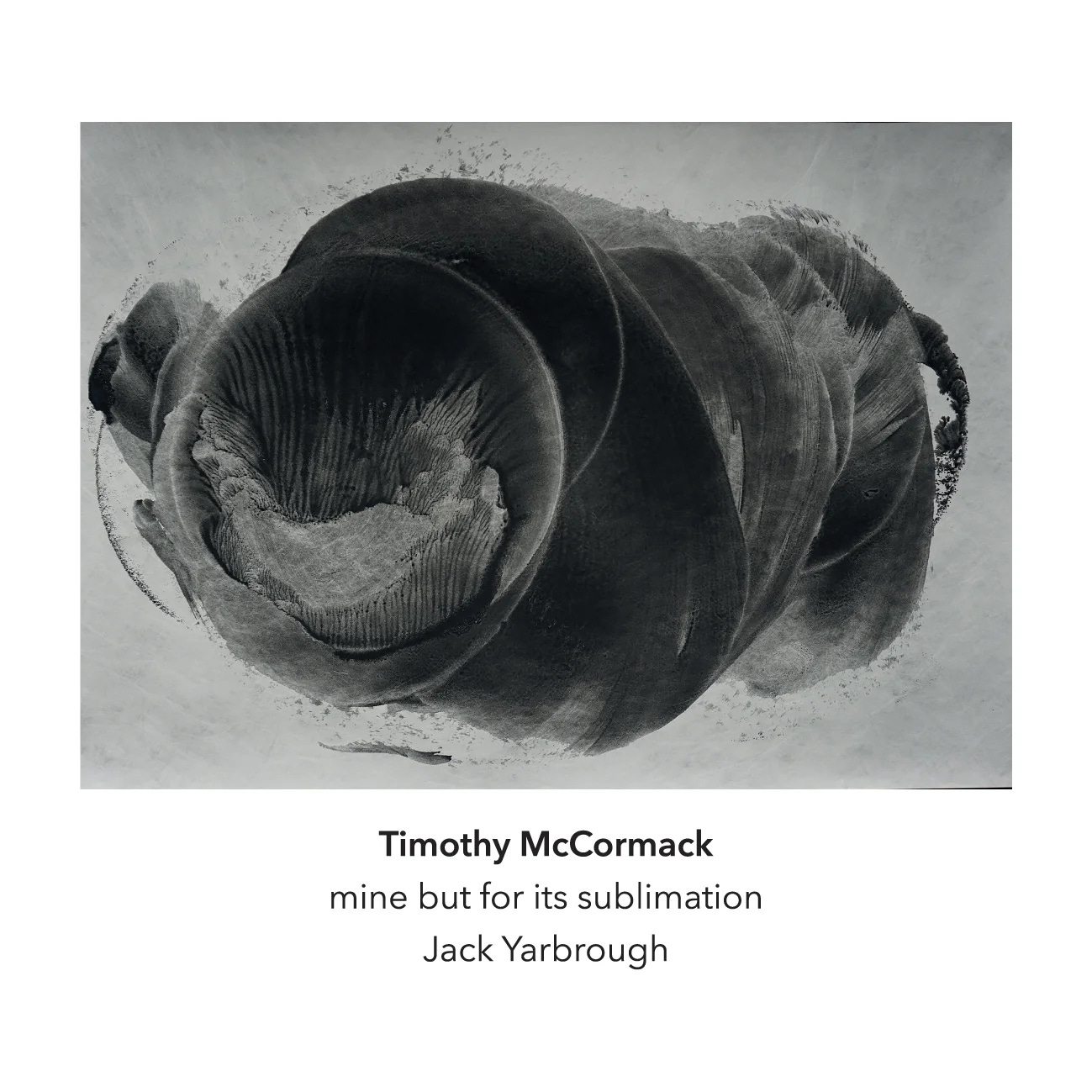

1 Timothy McCormack: mine but for its sublimation (another timbre)

Jack Yarbrough, piano

When I first encountered this sixty-four-minute piano solo through a video of Jack Yarbrough giving its premiere at the Boston Conservatory, I knew very quickly that it was something special. Tim’s music has fascinated me for years, but this was something else: the handling of the piano as a machine of resonance and attack (yes, all piano music is that, but this is almost nothing but that), the insights into the interlacing of touch and duration, the sheer inventiveness in escaping self-defined limits. And that is all before the defining twist midway through that the music has been gently steering you towards.

Tim has been on a journey towards clarity since the complexist experiments of his student years, but mine but … shows that he has retained every lesson about the significance of detail, the essential interrelationship of sound, instrument and body, and the necessity of boldness. Tim makes crystals (always has), in which the sharp detail of every moment is the point. The care with which this music is made is part of its character; it never rests on anything automatic, or semi-processual, or quasi-improvised. So when a copy of Yarbrough’s recording for another timbre arrived at my door, you can imagine my delight. Returning to it time and again has been an enduring pleasure of my year.

2 Leo Chadburn: Sleep in the Shadow of the Alternator (Library of Nothing)

The record Chadburn has been working towards for years, gloriously realised. See PurLis 1 for full write-up.

3 Evan Johnson: dust book (another timbre)

Marco Fusi, viola d’amore

Johnson’s discography has grown substantially in the last few years, all of it of interest. But this feels like the essential release: an hour of music divided into six panels that somehow manages to barely exist; that somehow manages to sustain and hold tension. The sound of motes rising from vibrating strings.

4 Linda Catlin Smith: The Plains (Redshift)

Cheryl Duvall, piano

Immediately one of my favourite works by Smith, a composer I admire enormously. The Plains is a sublime essay in taking a line for a walk, performed with stunning patience and control by long-time champion Duvall. See PurLis 4 for a write-up, and my interview with the pianist.

5 Ash Fure: Animal (Smalltown Supersound)

Lachenmann visits Berghain. Ash Fure’s Animal roars out of your speakers like a particularly dry Richie Hawtin track and continues its incessant throb for another thirty-eight minutes. It’s already thrilling, but the real revelation comes from seeing how it was made – as in this video from a live performance at IRCAM in 2024:

Crouched over two upturned subwoofers (an innovation pioneered in her immersive ‘opera for objects’ The Force of Things), Fure twists a sheet of corrugated plastic, literally surfing on sine waves to carve the pulse into elegant, phasing curves. It’s electronic music brought into the realm of physical performance; Fure talks of ending performances drenched in sweat. Lachenmann devoted himself to bringing the attitudes of electronic musique concrète to instrumental music. Fure has spoken of the impact his music has had on hers; now she is closing the circle back to electronics. A musique concrète instrumentale électronique, if you will?

6 Hannah Kendall: Shouting Forever Into the Receiver (NMC)

Ensemble Modern; Anne Denholm-Blair, harp; loadbang, Jonathan Morton, viola; Louise McMonagle, cello; Wavefield Ensemble

Another example of a composer reaching a place they have been heading to for a long time. Kendall started to attract notice in the mid-2010s for her skillfully made, if – for my money – slightly conservative works, of which 2017’s The Spark Catchers is a highlight. Since 2020, her music has transformed: an extended engagement with the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat has been part of that, and three pieces from her Basquiat-inspired Tuxedo series feature on this disc. The haunting, terrifying Shouting Forever Into the Receiver sets the tone, though: the enumeration of tribal populations, taken from the Book of Ezekiel and spoken through walkie-talkies, carries a chilling echo of the bureaucratic objectification and dehumanisation of the slave trade. The entry of a cloud of music boxes, mechanically and mindlessly plinking their way through ‘Ode to Joy’ and other classics of the Enlightenment, only magnifies the effect.

7 Ellen Fullman: Elemental View (Room40)

I’ve long known about Fullman as the inventor and purveyor of the Long String Instrument, and yes, there are plenty of its sharply citrus drones on display here. I wasn’t quite prepared for the shuddering, almost dubby (with further echoes of Appalachian folk) contributions of guitar and percussion duo The Living Earth Show. But of course, in the reverberating spaces of Fullman’s long strings, both make perfect sense. A superb collaboration, in a year that was full of them.

8 Hugues Dufourt: L’Origin du monde (Divine Art)

Marilyn Nonken, piano

The moment Dufourt steps out of the shadow of his peers? Time will tell, but he couldn’t ask for a better champion. Revelatory; see PurLis 3 for review.

9 Annea Lockwood: The Piano Works (Unsounds)

Xenia Pestova Bennett, piano

Until quite recently, history recognised at least three Annea Lockwoods, each of them different. There was the Annea Lockwood of burning and buried pianos; there was the Annea Lockwood of the early Glass Concerts; and there was the Annea Lockwood of the river soundmaps. (Perhaps, for the more attentive, there were also the feminist Annea Lockwood of Women’s Work and the Antipodean Annea Lockwood of Thousand-Year Dreaming.) It is gratifying, then, that the recent surge of interest in Lockwood’s music has also highlighted the coherence of her project, of listening and – especially – listening with. (The joy of doing so seems precisely the message of For Ruth, her ecstatic and sexy portrait of her late partner, Ruth Anderson, made through recordings of their first, flirtatious conversations and captured on 2023’s Tête-à-tête. The disaster of not doing so undergirds On Fractured Ground, a composition of field recordings from the Belfast ‘peace walls’, also released this year, on Black Truffle.) The Piano Works is an important contribution to this coming together, collecting pieces composed between 1993 and 2002, performed with force and vitality by Xenia Pestova Bennett.

10 Liza Lim/JACK Quartet: String Creatures (NMC)

Any new disc of Liza’s music is welcome around these parts, and this one is a doozy. The titular string quartet, a major work of her last few years, is partnered with one of her rare few other excursions into the genre, The Weaver’s Knot, plus works for solo cello and double bass, each of which involves its players doing ‘stringy’ things beyond their usual bounds. I said at the time how uncommon it is to have a new music portrait album that really hangs together as an album – from repertory to sleevenotes to sound (the fulfilment that comes when Rohan Dasika’s bass really opens up on The Table of Knowledge to close the disc), this is that rare thing: an object to be enjoyed entirely, in and of itself.

Bubbling under:

Natasha Barrett: Toxic Colour (Persistence of Sound); Raven Chacon: Voiceless Mass (Anthology of Recorded Music); Morton Feldman/Antti Tolvi: Intermission 6 (another timbre); Mark Fell: Psychic Resynthesis (Frozen Reeds); Michael Finnissy/Ian Pace: Piano Works (Métier); Horse Lords and Arnold Dreyblatt: Extended Field (RVNG Intl.); Eleanor Kampe: Breath. Play (Cruel Nature); Alex Paxton: Delicious (New Amsterdam).

Live review: LCMF at Wigmore Hall

I’ve always admired what Igor Toronyi-Lalic and Jack Sheen do with LCMF, for their curatorial chutzpah and attention to detail. They give a unique level of care to every aspect of the performance, and they have the courage to put on works no one else in London would come close to programming. This evening, those were Clarence Barlow’s patience-stretching, then patience-rewarding Im Januar am Nile – a work that, like a Stewart Lee routine, pushes all the way through annoying to become interesting again – and Hanne Darboven’s Opus 17a, funkily and relentlessly rendered for drums by George Barton.1 Often, boldness and refinement work in opposition, but it’s good nevertheless to go to an event that’s willing to have a crack at both, rather than retreat or give up.

And it can be done: see Eastman and Rzewski in 2016 or Ragnar Kjartansson’s An die Musik in 2017. Tonight wasn’t one of those nights, but it did have its moments. (With LCMF having been in a biennial format since 2022, this was essentially an ‘off’ year in any case: just the one concert rather than the full multi-day extravaganza. So I acknowledge that different rules apply.)

Those curatorial details often derive from subversions of or interventions into the performance ritual: ways of seating, lighting, presenting, ordering. The architectural and theatrical aspects of a production as much as its musical ones. In a space as hallowed as the Wigmore Hall, however, there’s only so much one can do. The concert’s best moments were those when ways were found to break into that rigidity. The first was Dominic Murcott’s player piano, set front and centre of the stage for the start of each half, like a nervous Angel Gabriel at the school nativity, before Murcott loaded it up with rolls of Nancarrow studies.2[2] (Two sets of applause: one for Murcott as human technician, one for the piano as mechanical executor.) Strangely harmonious with the hall’s Victorian architecture, it was also dramatically out of place in this temple to instrumental chamber music. Yet it sounded terrific, and looked even better, all shining brass and wood, the faces of its keys flickering up and down, white and black, like a pixel animation.

The second moment accompanied the trio of eighteenth-century dice game pieces by CPE Bach, Antonio Calegari and attributed to Mozart. These were generated live for four players of Explore Ensemble following the rules and materials set out by each composer. To gather the necessary numbers, Toronyi-Lalic and Elaine Mitchener walked up and down the aisles, passing a tray and two dice for members of the audience to throw. They were like servers in church, collecting the offertory. The dice were plastic but the trays steel, and they made a pleasingly repetitive sound that alternated from one side of the hall to the other, as much part of the music as the music itself.

Elsewhere, two songs by members of Jennifer Walshe’s invented cohort of Irish avant-gardists – Eyleif Mullen-White and Caomhín Breathnach – were on theme (the former a setting of Gulliver’s visit to the ‘Academy of Projectors’, Swift’s imagining of a kind of proto-LLM; the latter based on ‘the positions of the planets in the sky over Carrick during a total lunar eclipse’). But they were human inventions of an algorithmic composition, imagined versions of an automated act, so they sat slightly out of place.

Alongside Explore, Walshe also performed her own Slop Studies 2#a-7, an LCMF/Wigmore Hall co-commission that featured creating glitched amalgams of song and noise that were intercut with Dall-E prompts in the voices of an array of characters – ‘It’s a shark, but with three fins and the fins are legs’; ‘A knife cuts into a basketball but the basketball is made of cake’; etc. While much of the programme carried an air of novelty or fairground attraction (always a danger with this cabinet-of-curiosities-style programming), ending here sounded a much-needed note of critique.

Live review: London Sinfonietta play Miller, Saunders, White and Grisey

A week later, I watched Sheen conduct the London Sinfonietta at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. I suspect he had a hand in designing this concert too: there was a thoughtfulness to the evening that you don’t always see at Sinfonietta events. Grisey’s Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil was obviously the cornerstone, but the three pieces that preceded it – Cassandra Miller’s violin solo for mira, Rebecca Saunders’ Strirrings Still II and John White’s Drinking and Hooting Machine were brilliantly chosen. Who would have imagined White’s absurdist slice of process music from 1976 would make such a perfect bridge between two more recent meditations on dust and decay? But perfect it was. Miller’s brilliant for mira – an uncanny evocation of the voice of Kurt Cobain – beautifully anticipated Grisey’s more extended consideration of the death of civilisations.

I give out about how the Sinfonietta puts its concerts together sometimes, but tonight, they mostly got it right. Starting with a spotlit solo – then, when that’s finished, bringing the lights up on six distributed musicians who have crept invisibly into place – is an old trick, but a really good one. Having soprano Nina Guo join in on the White with her own bottle, rather than break the continuity with a soloist’s entrance for the Grisey that followed, was a new one, and also really effective. The only bump came between the Saunders and the White. I get it, you’ve got to transition from six musicians arranged around the auditorium to nineteen on stage. But to have everyone shuffle on in ones and twos over the course of several minutes is inexplicable, and it killed whatever energy that had been carefully nurtured up until then.

This was my third Grisey. I love this work deeply, and to begin with, I was troubled by Sheen’s interpretation. Those scales at the start that drift down like ash felt too broken, too jagged; as if the players weren’t warmed up sufficiently to flow in and out of each other’s sound. But eventually it grew on me. The greater air within the sound made it lighter. Sheen emphasised (as indeed does Grisey’s score) the upper partials of the harmonic spectrum; with less weight on the bottom end, the music almost floated in places. It is possible to make this music too morbid, too gluey; but here the extraordinary second movement gained the spring of a kind of Totentanz, a dimension I had not considered before. At times, the music approached the brink of completely falling apart, like so many fragments of Egyptian sarcophagi. Normally, that would be a damning assessment, but uniquely for this piece, it was a legitimate reading. Death haunts the Quatre chants in many layers; in this performance, the London Sinfonietta – who gave it its triumphant, valedictory premiere in 1999 – seemed almost to be memorialising a remarkable moment in music history, even as they realised the necessity of returning to it.

The previous London performance of Opus 17a was Michael Francis Duch’s, at Music We’d Like to Hear in 2012. Duch has written an extended reflection on learning the piece, and playing long duration works in general.

Numbers 3a, 20, 12, 36 and the extraordinary number 25, which through sheer density seems to wormhole the piano into a parallel sonic universe.